Ovarian Cystectomy

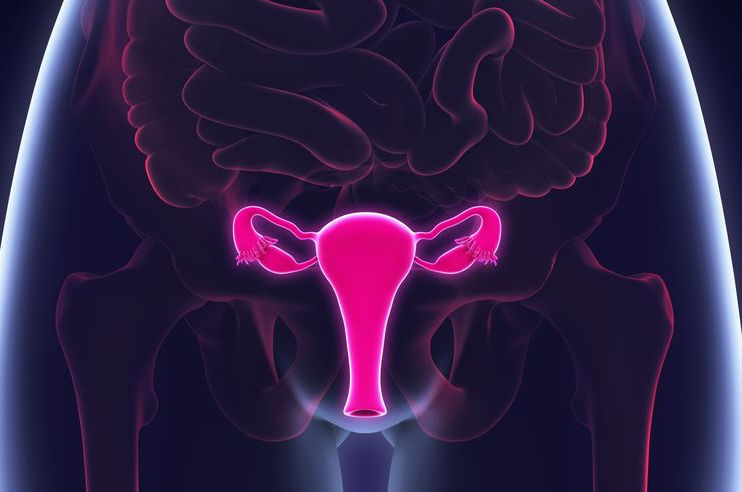

An ovarian cystectomy is surgery to remove a cyst from your ovary. Laparoscopic surgery is a minimally invasive surgery technique that only uses a few small incisions in your lower abdomen.

The normal ovary by nature is a partially cystic structure. Most ovarian cysts develop as consequence of disordered ovulation in which the follicle fails to release the oocyte. The follicular cells continue to secrete fluid and expand the follicle, which over time can become cystic.

The ovaries are the female pelvic reproductive organs that house the ova and are also responsible for the production of sex hormones. They are paired organs located on either side of the uterus within the broad ligament below the uterine (fallopian) tubes. The ovary is within the ovarian fossa, a space that is bound by the external iliac vessels, obliterated umbilical artery, and the ureter. The ovaries are responsible for housing and releasing ova, or eggs, necessary for reproduction. For more information about the relevant anatomy, see Ovary Anatomy.

Indeed, ovarian cysts were the fourth most common gynecologic cause of hospital admissions according to a late 1980s study by Grimes and Hughes. [1] Most cysts spontaneously resolve while some will persist. The persistent ovarian cysts are most likely to be surgically managed. The standard surgical approach to presumptively benign ovarian cysts is the laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy. Indeed, it is one of the most common procedures performed by the practicing obstetrician gynecologist.In this article, the pathophysiology of ovarian cysts is briefly reviewed to provide a foundation for understanding the ovary and benign cyst formation. The remainder of the article concentrates on the patient evaluation and surgical approaches to cyst removal.

Pathophysiology of ovarian cyst formation

Obstetrician-gynecologists and surgeons most commonly encounter 3 types of benign ovarian cysts. They include functional (follicular and corpus luteum) cysts, mature cystic teratomas, and endometriomas. Functional cysts form in reproductive-aged females during folliculogenesis and are either follicular or corpus luteal in origin. The cysts occur during the process of normal female reproductive physiology, hence their functional designation. The pathogenesis of follicular cyst formation is complex and is associated with the release of anterior pituitary hormones. In these cases, the traditional feedback mechanisms are not synchronized and the luteinizing hormone surge is muted.

Consequently, the oocyte is not released by the follicle, which in turn fails to involute and continues to grow, sometimes achieving cystic proportions. Corpus luteum cysts develop after ovulation through an unknown mechanism. They can become quite large and torsed and, thus, are more likely to be associated with pain and in some cases delayed menses. Some cysts autonomously function such as those associated with the McCune-Albright syndrome and can achieve large sizes.

Mature cystic teratomas (MCTs) or dermoids are actually benign germ cell tumors that are partially cystic. They can occur over a broad range of ages, yet more than 70% occur during the reproductive years. They are thought to develop from a single primordial germ cell that has completed meiosis I and is meiosis II-suppressed. [4] This theory is supported by the anatomic distribution of teratomas throughout the migration pathway of primordial germ cells from the yolk sac to the gonadal ridges. MCTs are composed of all 3 germ layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. They are usually unilateral, measure 2-4 cm in diameter, and are filled with thick sebaceous material, hair, calcifications and sometimes teeth (see images below). Some are even hormonally active. Unlike simple cysts, MCTs do not resolve spontaneously. Most require surgical intervention. They are more likely than other benign cysts to be associated with ovarian torsion.

Endometriomas are hormonally active ovarian cysts with the hormone changes corresponding to menstrual cycle phases. The origin of endometriomas has been controversial. Nezhat and coworkers have suggested that 2 types of endometriomas exist: primary and secondary. [8] According to the authors, primary endometriomas originate as invaginated surface endometrial glands. They develop slowly over time and rarely achieve sizes greater than 5-6 cm. They are quite difficult to remove from their fibrotic capsule at the time of cystectomies. Upon microscopic examination, both endometrial glands and stroma are identified. Secondary endometriomas originate in functional cysts, with some having their origins in a corpus luteum. These endometriomas are the classical chocolate cysts and contain dark blood (see image below). Secondary endometriomas can achieve quite large sizes and can be removed easily. Microscopic examination of a well-sampled specimen often reveals a corpus luteum, endometrial glands,andstroma.

Epidemiology

Ovarian cysts are quite common and involve all age groups, occurring in both symptomatic and nonsymptomatic females. [9] Six percent of 5000 healthy women in a study reported by Campbell et al had detectable adnexal masses on transabdominal ultrasound. Of these, 90% were cystic with most diagnosed as simple cysts. About 8% of premenopausal women develop large cysts that need treatment. According to National Institutes of Health estimates, 5-10% of women have surgery to remove an ovarian cyst. Of these cysts, approximately 13-21% are cancerous. Ovarian cysts are less common after menopause. Postmenopausal women with ovarian cysts are at higher risk for ovarian cancer

Indications

Absolute indications for ovarian cystectomy include the following: definitive diagnostic confirmation of an ovarian cyst, removal of symptomatic cysts, and exclusion of ovarian cancer. Additional indications include cyst size larger than 7.6 cm, cysts that do not resolve after 2-3 mo of close observation, bilateral lesions, and ultrasound imaging findings that deviate from a simple functional cyst. Note that both the patient’s age at the time of detection and as well as cyst type can influence surgical indications as reviewed below.

Fetal

Ovarian cysts in the developing fetus are more common than previously thought owing to their detection by antenatal ultrasound imaging. They have been identified on routine obstetrical ultrasound in 30-70% of fetuses, with the frequency increasing as gestation advances. They are usually unilateral and often resolve spontaneously. They originate as a consequence of ovarian stimulation from combined maternal and fetal gonadotropins. Surgical management, including cyst aspiration, is not usually indicated.

Neonatal

Ovarian cysts are thought to develop in neonates as a consequence of in utero hormonal stimulation . They are also more common than previously thought. Approximately 30% of neonates that underwent post mortem examination had ovarian cysts. Most neonates are asymptomatic with the cysts usually identified by ultrasound for unrelated indications. Many are simple cysts while others are complex, rendering a benign diagnosis more difficult. They often regress spontaneously in the first 4-5 postnatal months. Cysts measuring greater than 5 cm are of concern in this age group as they often torsed and can auto amputate. Bryan et al recommend aspiration to prevent torsion from occurring. Cystectomies are not usually indicated.

Prepubertal child

Ovarian cysts are usually seen in early childhood, age less than 6 yrs, and then again in the peripubertal period when the hypothalamic pulse generator is the most active. Gonadotropin stimulation of the ovary can cause some follicles to become cystic, with some cysts persisting. Mature cystic teratomas (MCTs) represent 90% of all ovarian tumors in this age group. Some cysts are autonomously functioning and may secrete hormones such as those seen in the McCune-Albright syndrome. The presentation in the young child varies. Asymptomatic patients may present with a palpable abdominal mass or increasing abdominal girth, while symptomatic children may present with increasing abdominal pain. McCune-Albright patients often present with signs indicative of precocious puberty. Cystectomies are not usually indicated since most resolve spontaneously.

Menarchal adolescents and adults

Benign ovarian cysts are quite common in menarchal adolescents and adults. Most regress within 2-3 months after detection, while others persist. Features associated with persistent ovarian cysts include cysts larger than 5 cm and complex morphologic findings on ultrasound.

The types of cysts that occur in reproductive age females differ from those encountered in early childhood. The most common benign ovarian cysts in this population are endometriomas and MCTs. Endometriomas are relatively common in the menarcheal teen and adult but are rarely seen in childhood. Patients with endometriomas often present with dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia. They may also present with pelvic pain, bloating, urinary frequency, menstrual irregularities, and/or constipation.

Young women with torsed ovarian cysts may present with nausea and vomiting along with acute abdominal pain and require surgical intervention. MCTs are the most common ovarian neoplasms in adolescents and account for nearly 70% of non-malignant ovarian neoplasms in females aged 30 yrs or younger. Patients with MCTs are usually asymptomatic and present with unrelated complaints. Indeed, in this setting, the detection of MCTs is often an incidental finding. The most common complaint in symptomatic patients is abdominal pain.

The most common benign ovarian cysts seen in pregnant women are MCTs and corpus luteum cysts. Acute complications have been reported to occur in less than 2% of these cases. Malignant ovarian cysts are infrequent in reproductive-age women, occurring in 3.6-6.8% of this population.

Postmenopausal

Unilocular small (< 5 cm) ovarian cysts in postmenopausal women have a low risk for malignancy. The frequency for malignancy increases between 6-39% in this population when the cyst is large (>10 cm), has complex architecture (multilocular, thick septae, irregular cyst walls), or persists. CA 125 measurements should be performed. Many postmenopausal women with large ovarian cysts are asymptomatic because menstrual irregularities and dysmenorrhea are no longer indices of pathology. When symptomatic, they can present with urinary frequency, constipation in addition to pelvic pain.

The image below depicts a multilocular ovarian cyst.

Anesthesia

General anesthesia is indicated for both the laparoscopic and robotic-assisted techniques since both of these procedures require the surgeon to create a pneumoperitoneum. Although either spinal or epidural anesthesia can be used for a laparotomy cystectomy, in most cases general anesthesia is used.

Complications

Complications of ovarian cystectomies are generally related to bleeding and inadvertent cyst rupture intraoperatively. Bleeding can usually be controlled with electrocautery. Ovarian preservation is essential for patients desiring future fertility, so not destroying a large portion of the ovary while achieving hemostasis is important. The addition of hemostatic agents such as Surgicel fibrillar, Evisel, Surgiflo (Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ), or Floseal and Gelfoam (Baxter International, Inc., Deerfield, IL) in some cases may be appropriate.

The frequency of intraoperative cyst rupture at laparoscopic cystectomy ranges from 6-27% and occurs more frequently than at laparotomy. Inadvertent spillage of the contents of an endometrioma may result in subsequent spread of the condition to other parts of the pelvis. Spillage of the contents of a cystic teratoma may result in peritoneal irritation, while the rupture of a malignant cystic structure is more serious. It may result in tumor dissemination and adversely affect the patients’ survival. [25] When spillage occurs, the pelvis should be copiously irrigated.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Phasellus ac aliquam velit. Phasellus dapibus cursus erat, quis consequat urna efficitur non. Phasellus cursus, erat quis mollis lobortis, urna risus hendrerit metus, id dictum metus purus vel magna. Nulla non purus sit amet arcu convallis egestas

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Phasellus ac aliquam velit. Phasellus dapibus cursus erat, quis consequat urna efficitur non. Phasellus cursus, erat quis mollis lobortis, urna risus hendrerit metus, id dictum metus purus vel magna. Nulla non purus sit amet arcu convallis egestas

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Phasellus ac aliquam velit. Phasellus dapibus cursus erat, quis consequat urna efficitur non. Phasellus cursus, erat quis mollis lobortis, urna risus hendrerit metus, id dictum metus purus vel magna. Nulla non purus sit amet arcu convallis egestas

COSMETIC SURGERY

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

COSMETIC SURGERY

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

COSMETIC SURGERY

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.